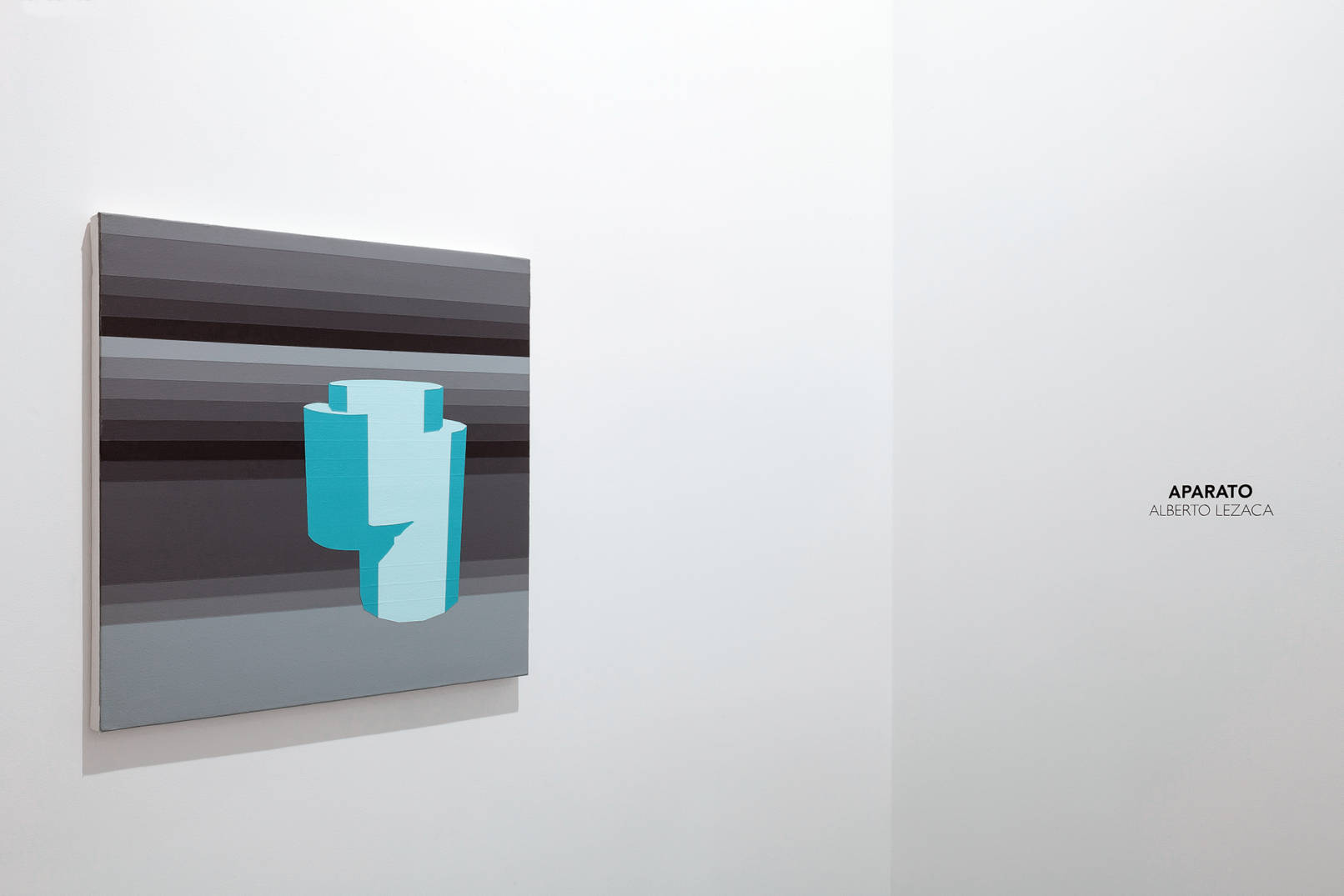

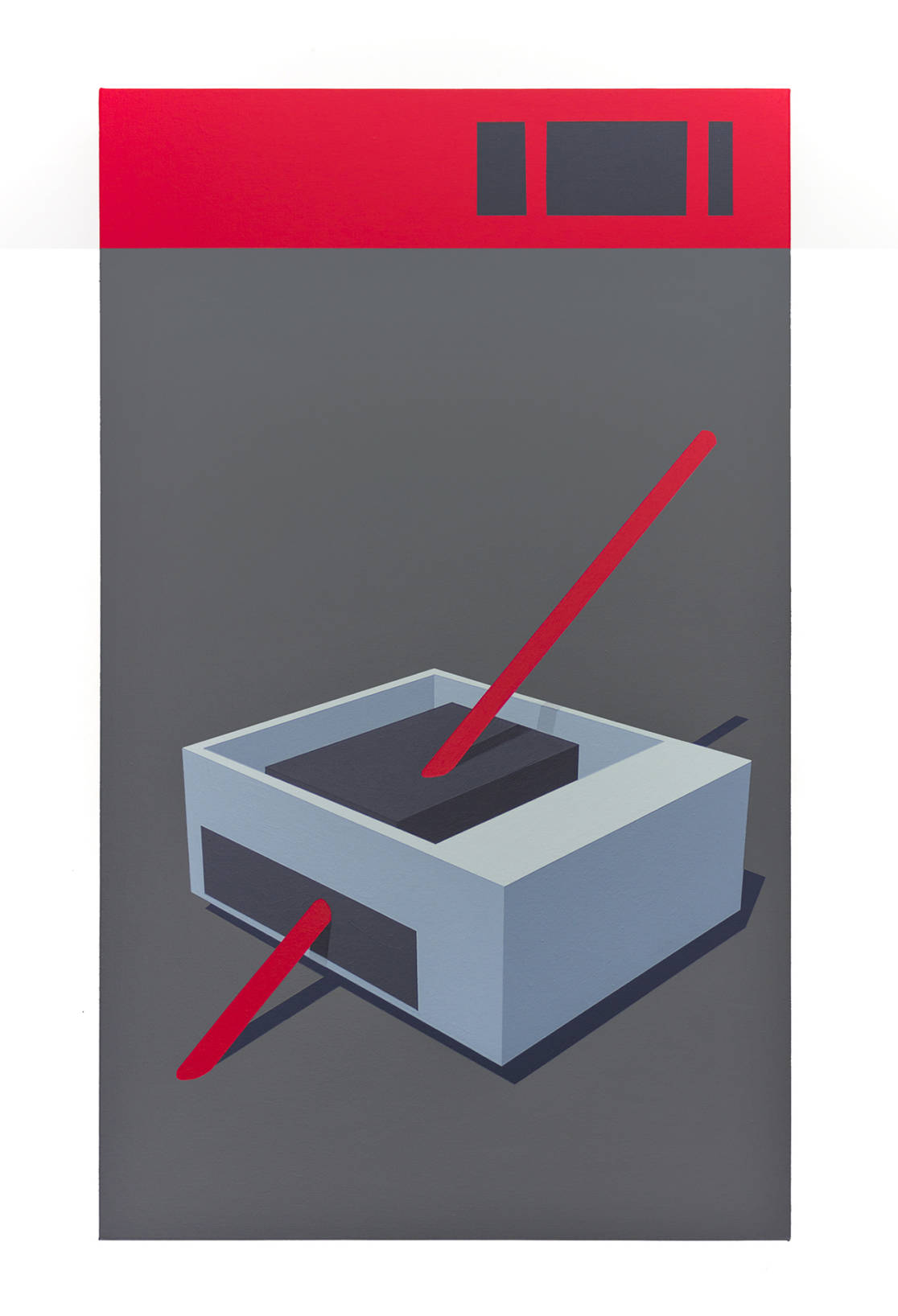

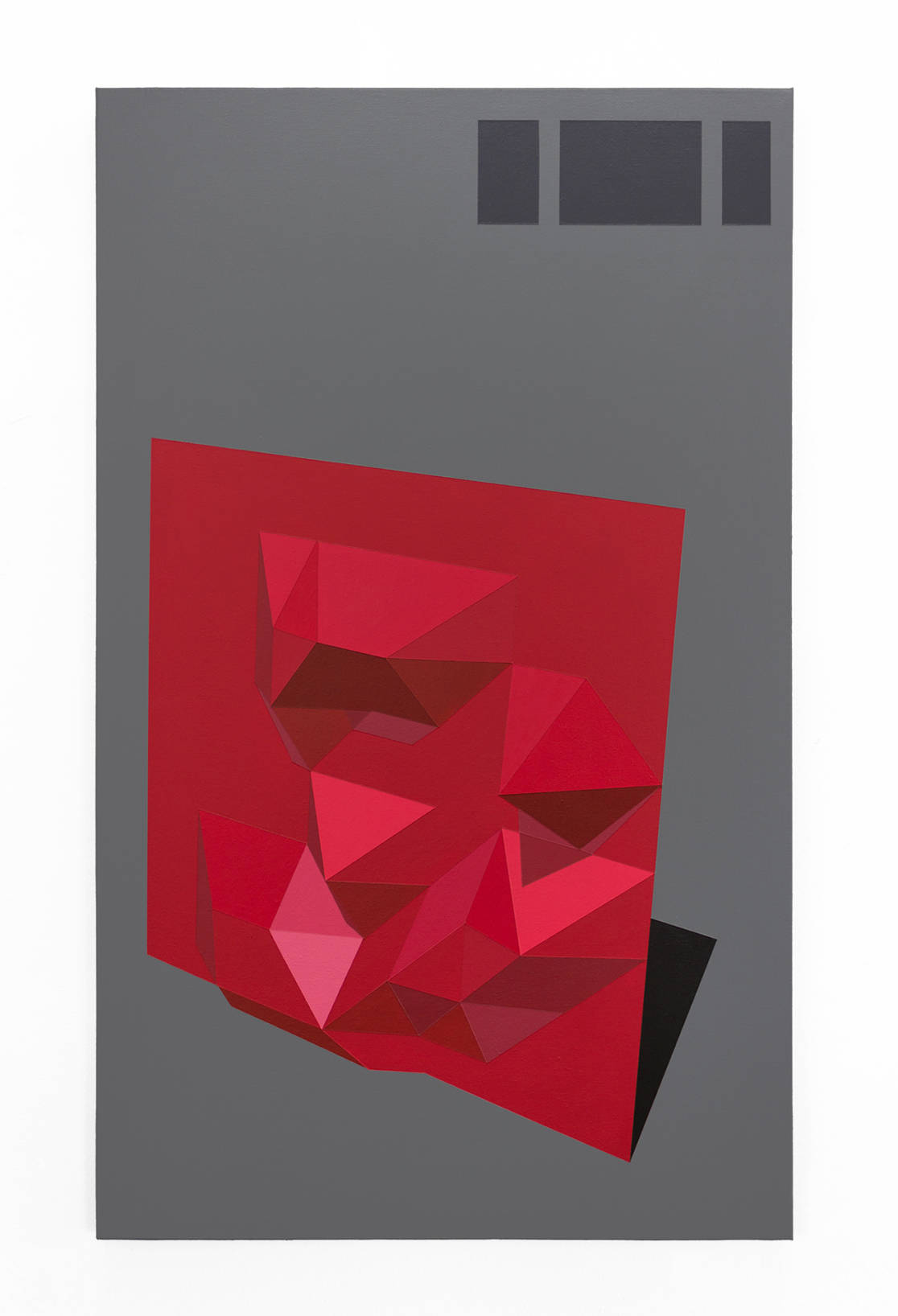

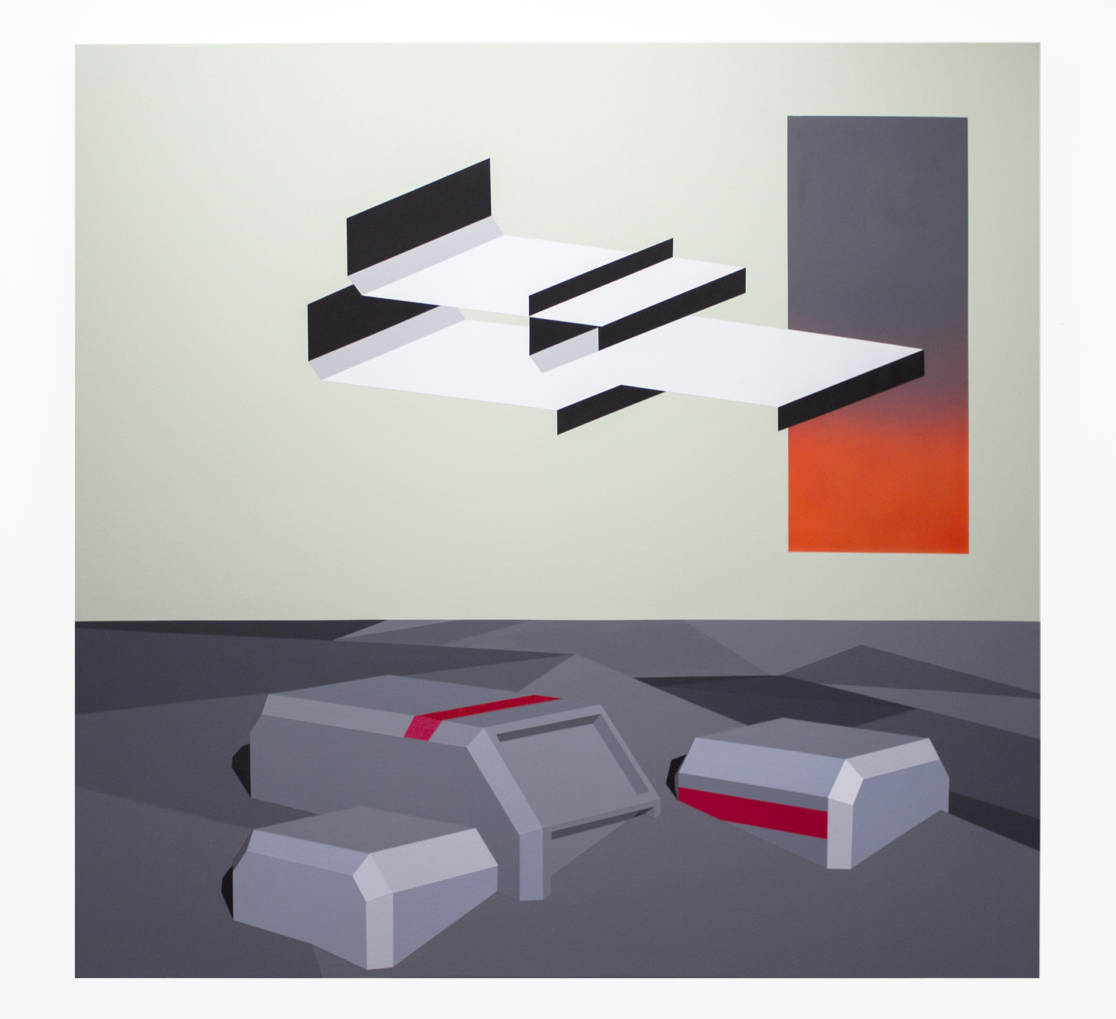

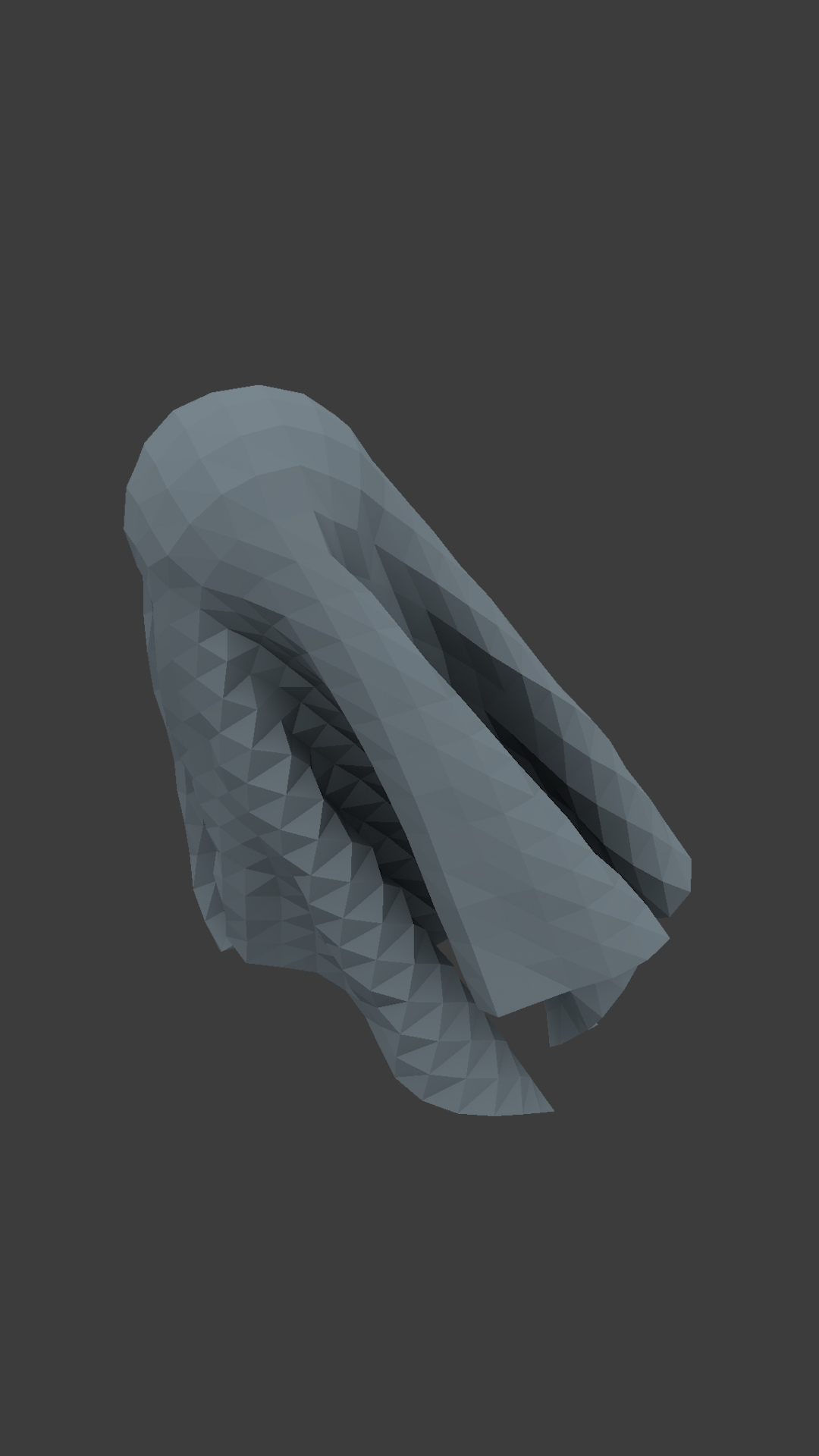

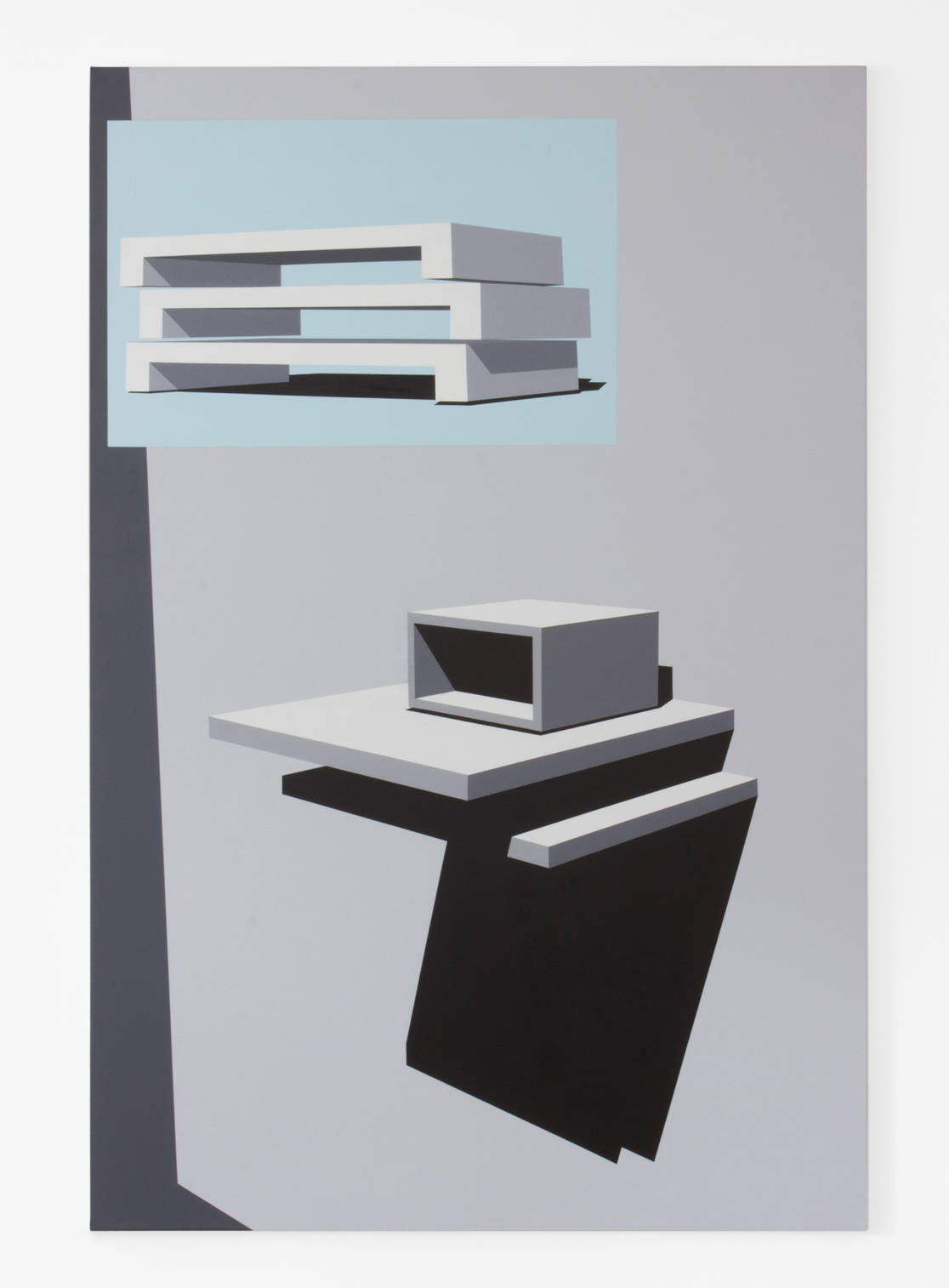

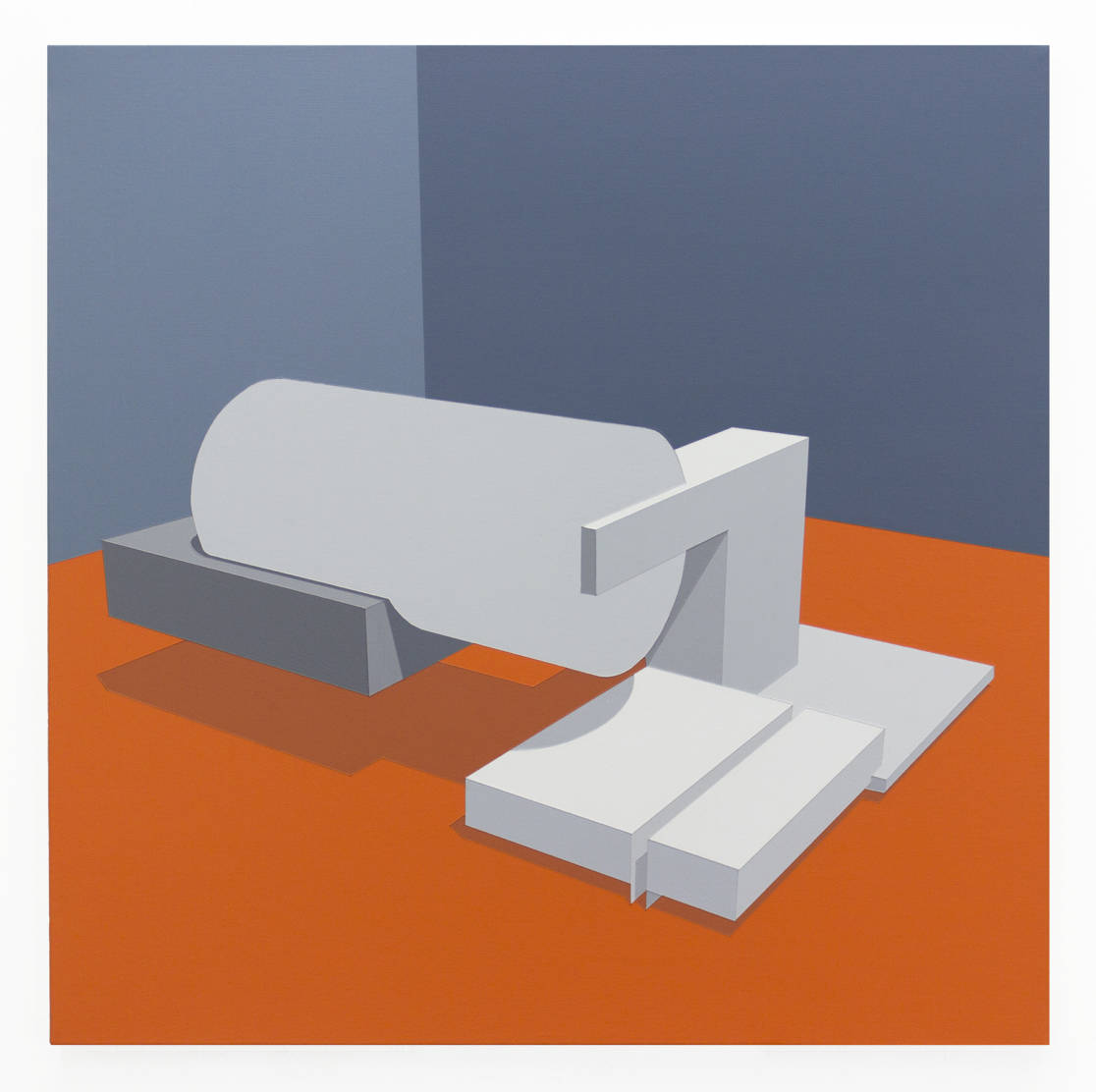

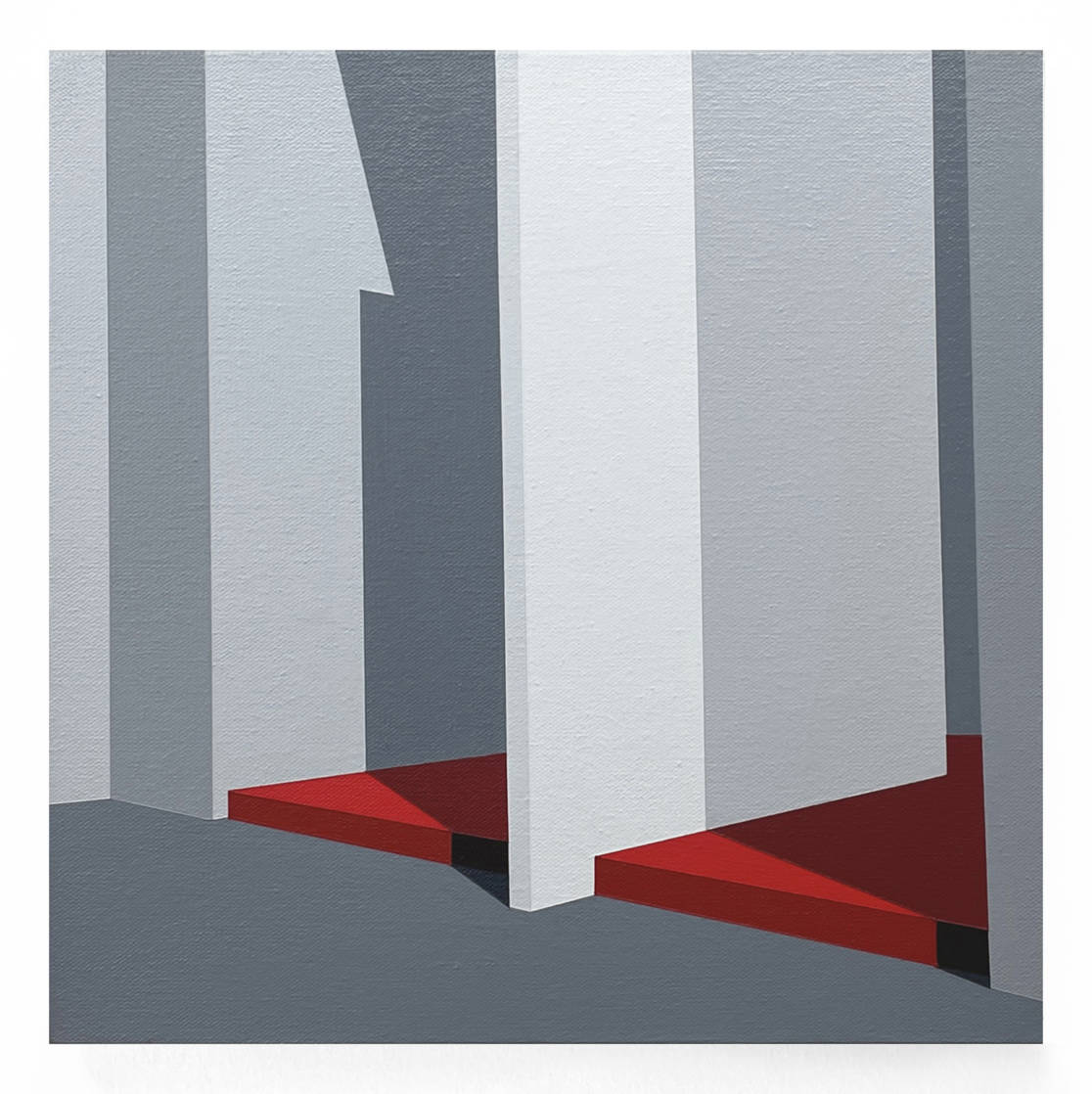

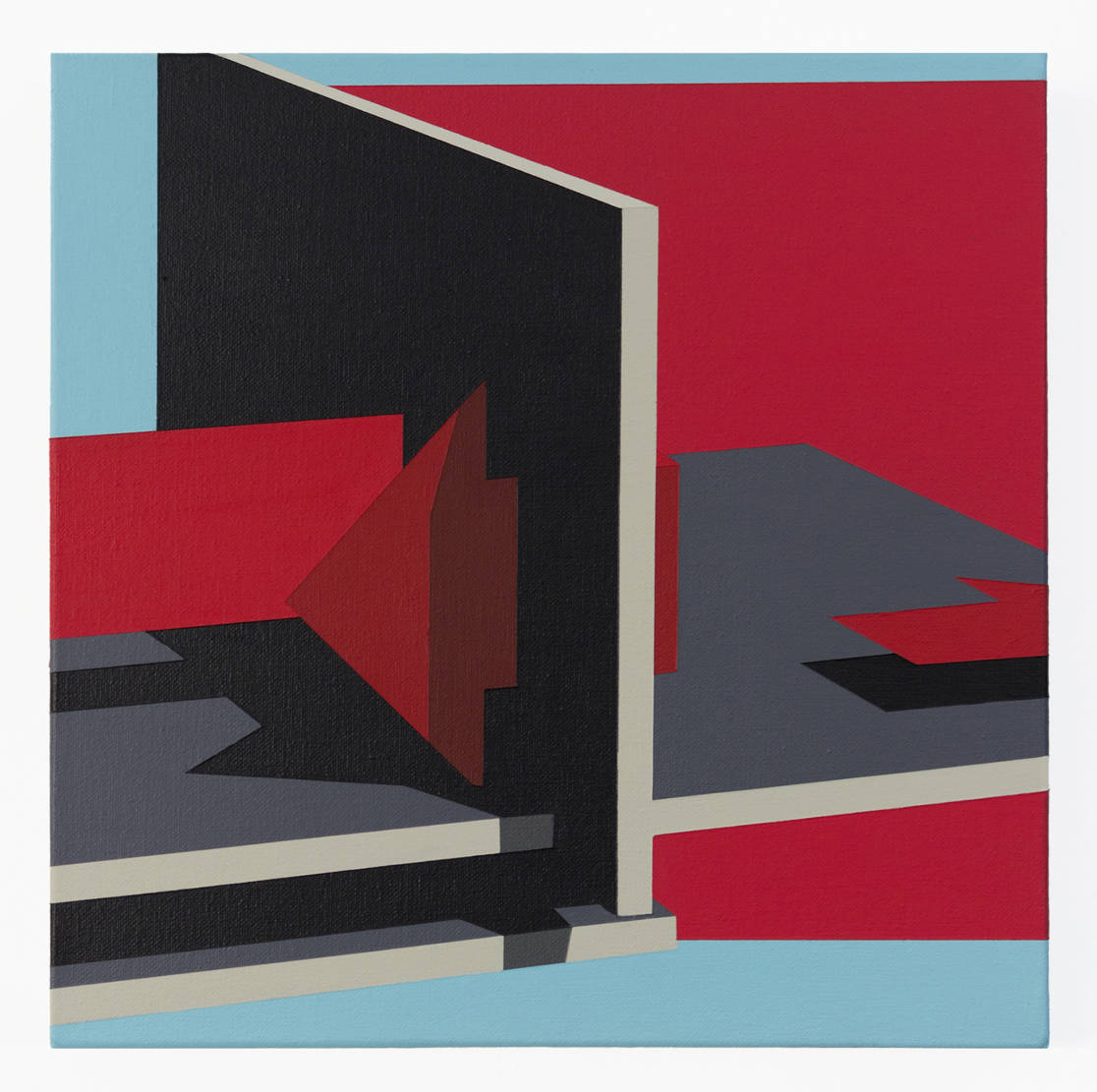

When we visit an exhibition by Alberto Lezaca, it seems as if we arrived to one of the apartments of the High Rise from J G Ballard’s novel. The visual references we receive, the flat colors, even the spectrum of color, the images’ mechanistic air make us think about a future that is between residential and dystopian. Immediately after that first impression we notice that the objects that surround us are useless and indifferent, contrary to any imaginable use, even impossible. In the early 1990s, Alberto Lezaca (Bogotá, Colombia, 1971) was part of a music band. Since he couldn’t find a drummer, he imagined that the sound he needed could be reproduced by a computer. He searched for an appropriate machine in several stores, and in almost all he received the same answer: computers are not good for making videos or for making music. But one day, when he had almost lost hope, a salesman told him: “you need an Amiga”. And that is how he discovered the mythical brand of Commodore computers that changed so many things at the end of the last century. An Amiga in this context is almost like talking to a companion robot, it is giving affection and personal value to a machine, to an “aparato” (apparatus). In Colombia “aparato” is a word that works for almost everything; it’s what mothers use to refer to any object that they want their son to hand her or to stop touching. An “aparato” is everything and is nothing. It is a word that precedes a precise and concrete denomination. It is a definition that hasn’t been finished. Unprecise. Open. Lezaca’s exhibitions are laid out as an immersion in a story. They are like suddenly entering in the middle of a narration that has already started and that will finish after you have left. The only thing you can do is trap the ideas, sensations, and impressions and try to decipher them to understand where you have been. However, the artist will constantly give you information that is incomplete, lacking, or contradictory to prevent you from satisfactorily closing any possible interpretation. Even his titles lead you to broaden the way you understand his works, instead of making them more specific. The way he executes his work is a sign of these apparent contradictions: he always starts by drawing on the computer, using programs that enable him to create a great number of possibilities of the same image. However, when he transfers it to the canvas, he does it rigorously by hand, using, if anything, a grid of those used in academic drawing. The outcome are paintings of objects that cannot exist and sculptures that seem to be flat. On the canvases, that remind us of blueprints or some kinds of comic strips, the colors, always cold, are barely contrasted with red, that is not able to warm up the composition. They appear in great masses, limiting shapes that take us to a certain mechanism, to an object we can only define as “aparato”. Useless and without purpose. On the other hand, the sculptures hide their tridimensionality by means of visual tricks. If you get close to them, it seems as if they were escaping. A good example of this is “Aparato Sánchez”, based on the portable x-ray machine invented by the Spanish Mónico Sanchez at the beginnings of the twentieth century. It was the first gadget of this kind that was greatly used during the world war. This fascinated Lezaca because since it’s portable, you can see inside the body. So his painting is initially based on the original object, but is divided in two fields: the top red one reminds us of the inside of the human body and the lower gray one, where the machine is located. The different parts of the object have lost their operating capacity, some by getting flat and others by developing relief. We don’t see how to operate it. It has no controls or buttons. It’s no surprise that the invention is named The Sánchez Portable Apparatus. This canvas works almost as a key that helps us interpret the rest of the exhibition, it gives us the fundamental clue that Lezaca’s exhibition (that is also transportable, from Bogotá to Madrid) works so we can see the interior, what is inside, discover what is hidden from us at first sight. Thus, the artist has built new walls in the gallery with grooves and openings that allow us to see the other side or perhaps insert a limb to find out what happens to it. The gallery transforms into a machine, into an “aparato”. In his work he questions modernity, or the idea of what is modern, from a rigorously antinatural point of view. Nothing in Lezaca’s work makes us suspect there is human or animal presence. The brushstroke disappears, and a machine could have applied the colors and drawn the lines. There is nothing left that is sensual or sensory. They are like parts of a catalog that intends to escape any naturalism or reproduction ideal of what is real. In fact, it seeks the opposite: to make evident that what is represented is artificial and by extension, the representation. In his paintings there is a fake utilitarianism, a deceiving functionality. Alberto Lezaca’s work insists on proposing a story about reality and an impossible fictional invention. He tries to create a new world and to do so, he starts with language, that is the fundamental basis. Because what has no name, doesn’t exist. It is still an “aparato”. Joaquín García Martín.

Madrid

Aparato

2023